Alabama Noir Read online

Page 6

* * *

Romy was still at their table when a muddied Bubba lumbered into the BBQ House, one arm behind his back.

"I was starting to think you found another frien—"

"I need your help," he told her. "I lost something. Probably won't change the outcome even if we find it, but I'm apologizing in advance if we don't. I brought you flowers."

He handed her a bouquet of landscaper flags.

CUSTOM MEATS

by Wendy Reed

West Jefferson County

Love bade me welcome . . . You must sit down, says Love, and taste my meat: So I did sit and eat. —George Herbert

Even over the deer's intestines, Jimbo could smell her: green apple shampoo and Juicy Fruit. He felt himself harden. All those careful habits formed over the years like flossing every morning, keeping his knives on the magnet when not in use, washing with bleach between each kill, and doubling his condoms were suddenly in danger. Cassie DeBardelaiwin, he sensed, was that kind of girl.

Jimbo did, however, manage to decline her order. Some things could not be compromised. It didn't matter if she wanted the Christmas sausage for her family's millworkers or the queen of England, Jimbo Sutt did not process any animal that hadn't been immediately field dressed and properly iced. No matter the season, Alabama heat advantages the maggots. Besides, Jimbo rarely took wild hogs because pork could be bought by the pound down at the Piggly Wiggly.

DeBardelaiwins weren't used to hearing no, but Jimbo held firm.

"You see that sign out front? It says Custom Meats. Not spoiled. Not cheap. Custom. I don't give customers anything I wouldn't eat myself."

Satisfied he'd made himself clear, he went back to finish the buck that had just been brought in. It was a beast of a specimen. Even with most of the blood drained out, it still felt warm to the touch. Large bucks required extra care around the neck, otherwise you could wind up having to quilt the hide together on the mount. Nothing ruined a trophy like patched trim. As a processor, he'd developed a reputation for the care he took, a trait seldom cultivated in an area now forced to survive through the short-sighted methods of strip-mining. Lately, though, Jimbo was achieving some renown for his white-tail testicle blend he sold in Mason jars that was said to be as potent as those little blue pills.

In the shop, Jimbo dressed and bled deer on a large slab of stainless steel surrounded by a drain his brother called The Moat and built right into the concrete floor. His new knife—the Jackal, according to the catalog from Zac Brown's metal shop—had cost a small fortune, and the verdict was still out whether it was worth it. Before long it would feel like an old friend, but now, as he wrapped his fingers around the carved handle, it felt stiff and more than a little strange. Having a girl standing around in the shop also felt strange, but oddly tolerable, as long as she didn't start up about the sausage again.

The scale read 212 pounds. This was what he called a jackpot buck because it would yield a twelve-point trophy plus a freezer full of quality venison. The girl gave no sign of leaving, so he steadied himself and tugged at the incision to widen it.

"You really set on giving out Christmas sausage?" he asked, tossing the question over his shoulder, wondering for the first time if she was jailbait.

She shrugged.

"Then I suggest Conecuh. It makes pretty good eating."

"That so?" Cassie said.

Jimbo was imagining what she wore under her skirt. It was made of denim—the same color as her eyes—and had a zipper down the front. He didn't respond to her question, if that's what it was, nor did he notice the way her lips curled or how she strutted right up to him until she stopped with her crotch at his face.

"So what do you eat," she asked, "besides meat?"

Jimbo pretended not to hear. He pretended to be engrossed in his work. He pretended not to wonder if her pubic hair also smelled like green apples. He pretended not to feel the jolt of electricity heating him up. Was she still trying to get him to take the hogs or was this something else? Was it some kind of game? Jimbo didn't know chess but he'd played poker. He lifted the buck's tail, revealing a thick stripe of white with a puckered hole of purplish skin in the center. He held the tail out of the way and suspended the Jackal's serrated blade just above the anus. He let the overhead light bounce off the metal and reflect onto Cassie's face. "It's made from old sawmill blades."

This was her chance to leave if she wanted to, before things got messy.

Cassie did not move.

Jimbo plunged the steel teeth about an inch deep and cut a circle around the anus. This was the point when most people left, or at least looked away. Cassie took a step back, but it was to get a better view. Jimbo pulled the rectum out a couple inches and closed it off with a rubber band. He reached into the belly—carefully, but firmly, so as not to puncture or damage anything—and pulled out the entrails with the intact rectum, like a magician with a scarf. Bowel leakage, like maggots, always ruins meat. With two fingers on either side of the blade, Jimbo reached inside, toward the deer's throat, and threaded the lungs out from between the ribs, reading the bones like braille as he went. Even a single bump could signal TB. And with one case already reported this season by Fish and Wildlife, you couldn't be too careful.

Cassie'd begun to breathe hard, but her color looked good. If she hadn't fainted yet, he guessed she wasn't going to.

"What's next?" she asked.

Jimbo stood up and a couple strands of blood or something stuck to his forearm. Color bloomed across her cheeks—not the blush of embarrassment but the flush that comes from standing close to a fire. In heels, she'd be taller than him.

"Ice. Go roll that cooler over here," he said. "It's full."

When she reached the Igloo, she hesitated and made sure he was watching, then she straddled the handle, slowly lifting it up until it disappeared beneath her skirt. Jimbo wasn't sure whether to keep watching. She locked eyes and stared squarely at him, like she was lining up invisible crosshairs. It was impossible, at that moment, to tell who had whom in their sights. That her panties dropped to the floor without being touched or tugged didn't strike Jimbo as anything other than good fortune.

"Maybe I need to cool off," she said, and tossed her panties into the ice chest.

Her grin beat all he'd ever seen. And he'd seen his share of women. Having to raise his brother took certain sacrifices but it hadn't turned him into a monk. Rather than wasting a whole evening on the rigamarole of dating, he preferred to buy off a menu, always glad they charged by the hour and not by the pound.

Cassie gave her hips a slow, final swivel, before she rolled the chest over to Jimbo. As she opened the lid, she bent over farther than Jimbo thought humanly possible and spread her legs. At that moment, it was Jimbo who was in danger of fainting. If Cassie'd asked him to reconsider making sausage for DeBardelaiwin Steel right then, he might have said yes.

The Jackal still lay beside the entrails. Not only did he neglect to put it up, he also didn't wash his hands before he handled the ice. Contamination was the last thing on his mind, fear having vanished from his regular radar. In one seemingly fluid motion, Jimbo crammed the cavity full of ice and was done. It was the fastest he'd ever packed a deer, and probably the only time in the history of West Jefferson County that lingerie and ice had been thusly juxtaposed.

* * *

Jimbo hadn't expected to see Cassie again. The DeBardelaiwins lived over the mountain. They did not associate with the likes of the Sutts. So when she kept coming back, he chalked it up to one of several flukes in a fluke-filled season: the albino doe with horns that Jimbo spotted on the way back from Medical West, where his brother Darrell took his regular treatments; the two-headed fawn found behind the sheriff's woodpile; and Darrell graduating to the group home.

Cassie came around for about a month and a half and then without a word stopped. Jimbo wondered what he'd done but he hadn't asked any questions while she was there, so he left it at that. He'd been half expecting not to see her aga

in, every time she'd left, which he told himself was fine, for the best really, because Sutts didn't do commitment. He'd heard the tales of his grandfather and bore the scars from his own father. He knew most men didn't like playing house anyway. They just did it because.

* * *

The following autumn arrived like a bobcat in heat—hot and bothered, foretelling storms that would level a high school and suck up the steeple from Mud Creek Baptist, spitting it out over at the Black Diamond, right on top of the tipple. Cassie, Jimbo'd heard, had gone off up north, where the DeBardelaiwins were from. To discourage thinking about her, he kept a piece of bamboo in his pocket that he rammed under a fingernail when his thoughts got out of hand.

One evening, Darrell was in the shop listening to something he called music, while Jimbo sharpened his favorite blades. Having Darrell move back in might offer more distraction.

Even over the boom box, the long whine of a car horn out front was loud. It was Cassie. Her windows were down, and her eyes looked wild. A smear of blood on her cheek made visible by her dashboard light.

"I didn't see it. Suddenly it was just there, right in front of the car. And then it was staring right at me. It didn't move. Oh God, it was awful. Just awful." Her voice broke but she didn't slow down. "What was I supposed to do? I didn't know what to do. What else could I do? I put it in my trunk." She lowered her head but raised her eyes. "I couldn't think."

The trunk was up.

A doe. Probably a yearling. What a pity. It looked like it'd been healthy, but now it was mostly dead, its legs nothing but a tangled mess. Clearly, the doe was suffering.

Jimbo tried to feel sorry for it, but all he could think about was Cassie. It'd been how many months—six or seven? He'd lost count on purpose and still, his first reflex was to snatch her out of the car and bend her over the hood. He wanted to bury himself inside her so she could never leave again. He wanted to tell her everything he'd imagined doing to her during those long nights he spent waiting, wondering if he'd ever see her again.

But Darrell was there.

Probably best anyway.

"How long ago?" he asked, trying to sound matter-of-fact, trying to hide his real question: Where were you when you hit it?

Cassie belonged in a different world and could never stay in his. He knew it, but he didn't have to like it.

Jimbo looked from the doe to Darrell and mouthed, Let's get it inside. He grabbed the front legs, motioned for Darrell to get the back legs, and whispered, "On three." As they lifted, Jimbo called from behind the car, "Happens all the time."

Too wounded to struggle, the doe's eyes rolled back in fear. How far did Cassie drive to bring me this deer? Was she already out this way? How long has she been back in Birmingham? Did she come to see me? The doe felt more awkward than heavy, and though nothing about Cassie should've surprised him, Jimbo couldn't help being impressed that she'd wrangled the wounded doe into the trunk all by herself. Everything in Jimbo strained toward the driver's side of the car. What harm could one whiff do? But he pushed Darrell and the doe in the opposite direction. "We've got it from here," he said, adding, "It's on the house," so she wouldn't come inside and try to pay.

If he was lucky, Cassie would drive off, out of his life for good. But luck wasn't what he craved.

Too weak to put up much of a struggle, the doe merely twitched her ears when placed on the slab; Darrell, Jimbo noticed, had begun trembling.

"Why don't you go close the trunk?" Jimbo said. "Tell her she can leave."

Despite all Darrell's medical treatment, he was still at risk of going berserk if he got upset. Their father had called him an idiot. The doctors couldn't seem to decide what to call him and had created what Jimbo called the Darrell Alphabet inside a folder more than two inches thick, starting with autism and ending with a syndrome that sounded like zucchini. But Jimbo had always just thought of Darrell as different, as he always would.

It occurred to him that something about the doe was different too. When he sliced into the jugular, the fat layer felt thick. She's pregnant. He wondered where Cassie had touched the doe. Maybe it still smelled like her. Does she still even use green apple shampoo? As he leaned down to sniff, he heard a car door close. If Cassie came in now, Darrell would follow her in and see the doe's throat. He wouldn't understand why Jimbo had cut it. Better take Darrell on back to the group home now. Let the doe bleed in the meantime.

But Darrell was not outside, and Cassie's car was gone. Damn electric cars. Their silence gave Jimbo the creeps. Maybe Darrell went on into the house after Cassie left, but he checked and it was empty. Darrell wouldn't have gone with Cassie, would he? He steered clear of strangers. Even ones with long blond hair. Maybe she'd won him over with Juicy Fruit, the only gum Jimbo had been able to get Darrell to chew.

Jimbo walked back to the shop. Ordinarily, he hung yearlings so their narrow bellies stretched before dressing, but on the off chance that this one was pregnant, he decided not to move it from the slab. As soon as he inserted the knife, there was a tiny burst of fluid and then a hoof popped out. Another followed. Of all the deer he'd processed, not a single one had ever been pregnant. Maybe he'd cut her throat too quickly. Too late now. He sliced through the skin and, for the first time in all the years, felt like he was trespassing. Half of him was appalled at what he was doing, but the other half was too curious to stop.

Out came a fawn that looked coated with plastic, like it'd been vacuum-packed for freshness. Two dark-pink balloon-looking things glistened with wetness. The placentomes. A hoof moved. It was alive.

Jimbo tried to think what to do next. He grabbed some shop towels, wet them, and began rubbing the fawn. How hard should he rub? He slid the fawn away from the doe and alternated between light and hard strokes. He'd had to pound hard on Darrell that time with the hot dog. When it finally popped out, it had been Jimbo who cried. Darrell had toddled off as if nothing had happened.

Jimbo tried not to think about those early days with Darrell.

* * *

"This is your brother—Darrell Sutt," his father had said, like Jimbo might not remember his own last name. It was the first time Jimbo had seen his father that year, and as usual, James Sutt Sr. was drunk. Soon as he started sobering up, he was gone again. Jimbo'd practically raised himself and now he was saddled with raising someone else too. He'd tried to find out who Darrell's mother was but hadn't gotten far. If nothing else, Darrell'd been a good excuse to quit school. Most things, he learned the hard way. But they'd survived and because the woods were so full, not once had they gone hungry. Or taken charity, because Jimbo discovered hunters would pay good money for him to process their kill—enough for Darrell to get treatment at the hospital and eventually be admitted into the special school.

* * *

Maybe the fawn would turn out normal. With its blunt little button nose, tiny white hooves that hadn't yet blacked, it looked so perfect. Tufts of hair and white spots scattered down the spine like pearls. It was startlingly beautiful and radiated a kind of luminescence that encircled the body like a halo. Could the fawn breathe? Did Jimbo need to peel the shiny stuff off?

Despite knowing just about everything there was to know about killing and processing deer, he knew nothing about their birthing. With Darrell and the Sutt track record, the last thing Jimbo needed was to become a father. Nothing about Darrell had ever been normal. He hadn't even come with a birthday. Jimbo'd made that up too.

Images flashed through his mind: Darrell screaming in that makeshift pen. Darrell covered in red bumps. Darrell slamming his head on the floor. Darrell turning blue. Darrell falling into the fire. Darrell's chest not moving for such a long time. But he was about to turn nineteen; they'd both survived.

* * *

Beginning with the nose, Jimbo worked at the spider weblike covering, and was making his way toward the tail when he sensed someone watching. He hadn't heard anyone drive up. Damn electric cars. In his peripheral vision stood a woman who looked like Cassie except she

was too round.

"Darrell asked me to take him back, so I did. It was the least I could do." Her voice sounded flat and sleepy, but it was the most beautiful music in the world.

He couldn't take his eyes away from her swollen belly. It looked liked she'd swallowed a basketball. Cassie was staring at the fawn. "It was pregnant too?"

Pregnant.

"Here, let me help." She kneeled down and took a towel. "Your brother is sweet. I've always heard he was crazy but he seems nothing but nice." She wiped at the fawn's eyes and nose.

Realizing she was pregnant had paused Jimbo's brain. He couldn't think. There were things he needed to say, but breathing was about all he could manage. The noise inside his ears grew into a roar. Talking hadn't exactly been their thing, yet over the weeks they'd spent together, he'd confided a couple things about Darrell and their father. She hadn't said much about her own father but Jimbo gathered that Josiah DeBardelaiwin kept Cassie in a gilded cage.

Jimbo grabbed her by the wrist.

"Let me go," she said, pulling away and trying to stand, but he squeezed until she gave up. She dropped the towel.

"Is it mine?" He wasn't sure which answer he wanted—for it to be his or someone else's.

Instead of getting up, she lifted the fawn's head between her hands. "It's none of your business."

"You saying it ain't mine?" He suddenly knew which answer he wanted.

She blew into the fawn's nose. "I'm saying it's none of your business." She took a deep breath and blew again. The fawn's face twitched. "Did you see that? It moved. Now what do we do?"

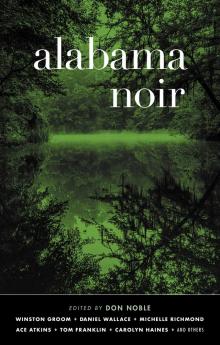

Alabama Noir

Alabama Noir